Hash and range sharding

Sharding is the process of breaking up large tables into smaller chunks called shards that are spread across multiple servers. Sharding is also referred to as horizontal partitioning, and a shard is essentially a horizontal data partition that contains a subset of the total data set, and hence is responsible for serving a portion of the overall workload. The idea is to distribute data that cannot fit on a single node onto a cluster of database nodes. The distinction between horizontal and vertical comes from the traditional tabular view of a database. A database can be split vertically, where different table columns are stored in a separate database, or horizontally , where rows of the same table are stored in multiple database nodes.

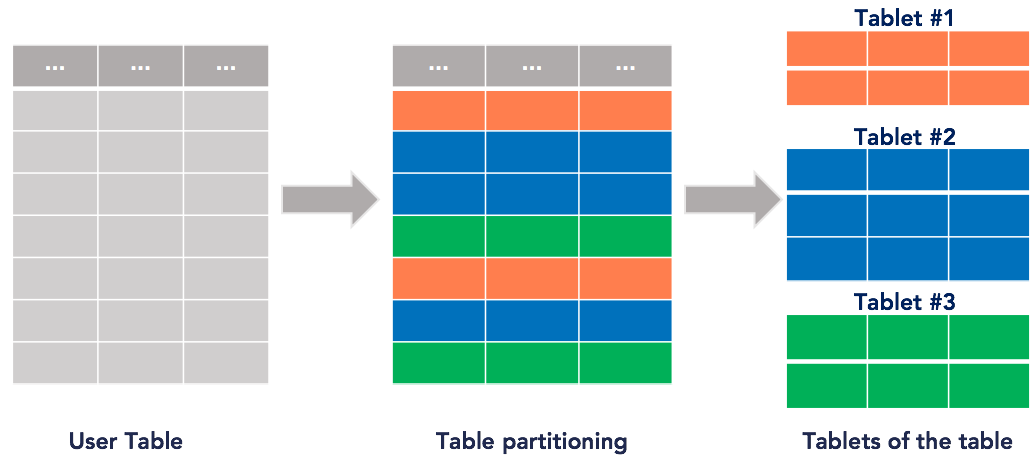

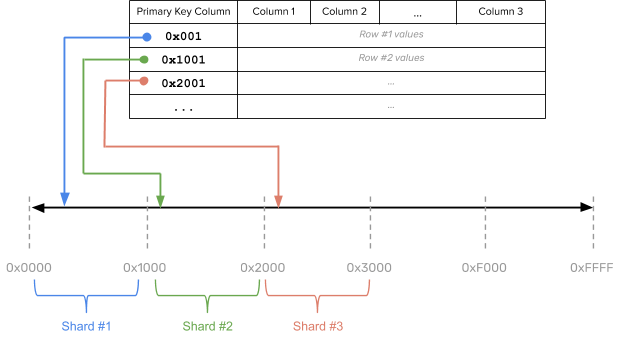

User tables are implicitly managed as multiple shards by DocDB. These shards are referred to as tablets. The primary key for each row in the table uniquely determines the tablet hosting the row (that is, for every key, there is exactly one tablet that owns it), as per the following illustration:

For information on sharding, see the following blog posts:

-

Analysis of four data sharding strategies when building a distributed SQL database

-

Overcoming MongoDB sharding and replication limitations with YugabyteDB

YugabyteDB currently supports two ways of sharding data: hash (also known as consistent hash) sharding and range sharding.

Hash sharding

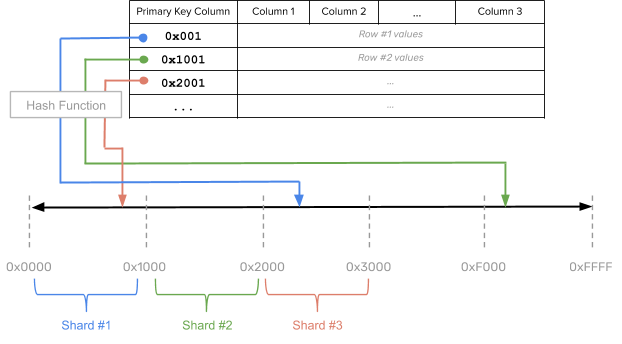

With hash sharding, data is evenly and randomly distributed across shards using a sharding algorithm. Each row of the table is placed into a shard determined by computing a hash on the shard column values of that row, as per the following illustration:

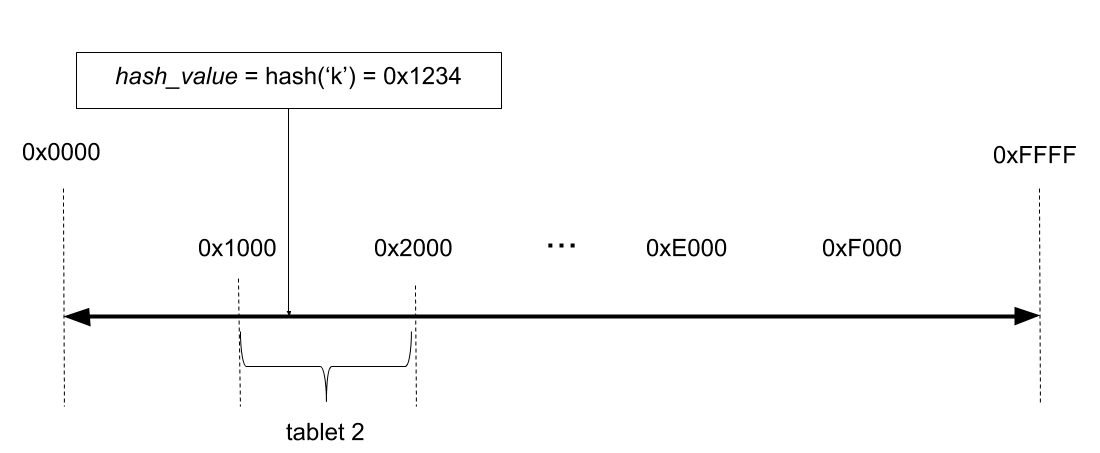

The hash space for hash-sharded YugabyteDB tables is the 2-byte range from 0x0000 to 0xFFFF. Such a table may therefore have at most 64K tablets. This should be sufficient in practice even for very large data sets or cluster sizes. As an example, for a table with sixteen tablets the overall hash space [0x0000 to 0xFFFF) is divided into sixteen subranges, one for each tablet: [0x0000, 0x1000), [0x1000, 0x2000), … , [0xF000, 0xFFFF]. Read and write operations are processed by converting the primary key into an internal key and its hash value, and determining to which tablet the operation should be routed, as demonstrated in the following illustration:

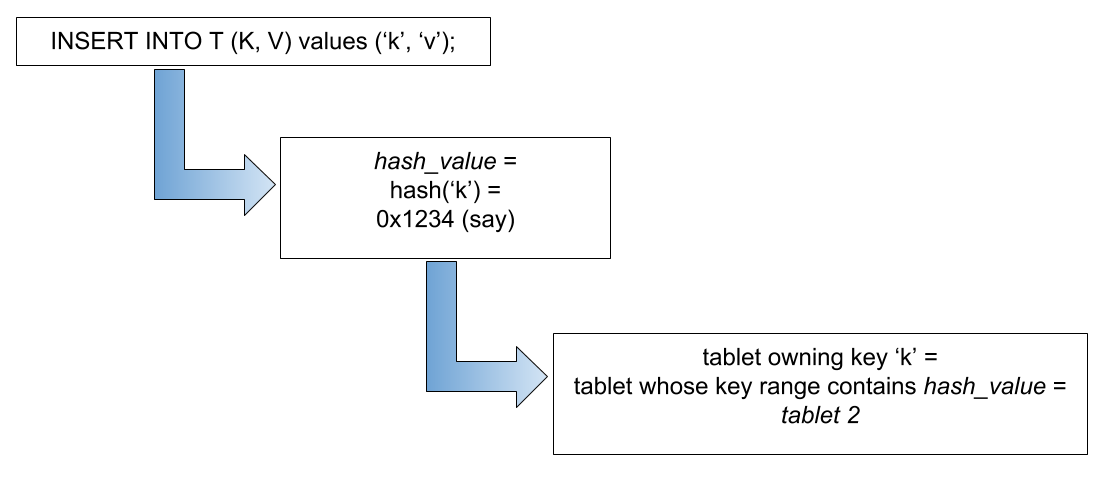

The insert, update, upsert by the end user is processed by serializing and hashing the primary key into byte sequences and determining the tablet to which they belong. Suppose a user is trying to insert a key k with a value v into a table T. The following illustration demonstrates how the tablet owning the key for the preceding table is determined:

Examples

The following example shows a YSQL table created with hash sharding:

CREATE TABLE customers (

customer_id bpchar NOT NULL,

company_name character varying(40) NOT NULL,

contact_name character varying(30),

contact_title character varying(30),

address character varying(60),

city character varying(15),

region character varying(15),

postal_code character varying(10),

country character varying(15),

phone character varying(24),

fax character varying(24),

PRIMARY KEY (customer_id HASH)

);

The following example shows a YCQL table created with hash sharding only, (an explict syntax for setting hash sharding is not necessary):

CREATE TABLE items (

supplier_id INT,

item_id INT,

supplier_name TEXT STATIC,

item_name TEXT,

PRIMARY KEY((supplier_id), item_id)

);

Advantages

This sharding strategy is ideal for massively-scalable workloads because it distributes data evenly across all the nodes in the cluster, while retaining ease of adding nodes into the cluster. Algorithmic hash sharding is also very effective at distributing data across nodes, but the distribution strategy depends on the number of nodes. With consistent hash sharding, there are many more shards than the number of nodes and an explicit mapping table is maintained to track the assignment of shards to nodes. When adding new nodes, a subset of shards from existing nodes can be efficiently moved into the new nodes without requiring a massive data reassignment.

Disadvantages

Performing range queries could be inefficient. Examples of such queries are finding rows greater than a lower bound or less than an upper bound (as opposed to point lookups).

Range sharding

Range sharding involves splitting the rows of a table into contiguous ranges that respect the sort order of the table based on the primary key column values. The tables that are range sharded usually start out with a single shard. As data is inserted into the table, it is dynamically split into multiple shards because it is not always possible to know the distribution of keys in the table ahead of time. The basic idea behind range sharding is demonstrated in the following illustration:

Examples

The following example shows a YSQL table created with range sharding:

CREATE TABLE order_details (

order_id smallint NOT NULL,

product_id smallint NOT NULL,

unit_price real NOT NULL,

quantity smallint NOT NULL,

discount real NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (order_id ASC, product_id),

FOREIGN KEY (product_id) REFERENCES products,

FOREIGN KEY (order_id) REFERENCES orders

);

YCQL tables cannot be created with range sharding. They can be created with hash sharding only.

Advantages

Range sharding allows efficiently querying a range of rows by the primary key values. Examples of such a query is to look up all keys that lie between a lower bound and an upper bound.

Disadvantages

At scale, range sharding leads to a number of issues in practice, some of which are similar to that of linear hash sharding.

Firstly, when starting with a single shard implies only a single node is taking all the user queries. This often results in a database warming problem, where all queries are handled by a single node even if there are multiple nodes in the cluster. The user would have to wait for enough splits to happen and these shards to get redistributed before all nodes in the cluster can be used, creating an issue in production workloads. This can be mitigated in some cases where the distribution of keys is known ahead of time by presplitting the table into multiple shards, however this is hard in practice.

Secondly, globally ordering keys across all the shards often generates hot spots, with some shards getting significantly more activity than others and the node hosting these shards becoming overloaded relatively to other nodes. While hot spots can be mitigated to some extent with active load balancing, this does not always work in practice because by the time hot shards are redistributed across nodes, the workload could change and introduce new hot spots.