Persistence

Once data is replicated using Raft across a majority of the YugabyteDB tablet-peers, it is applied to each tablet peer’s local DocDB document storage layer.

Storage model

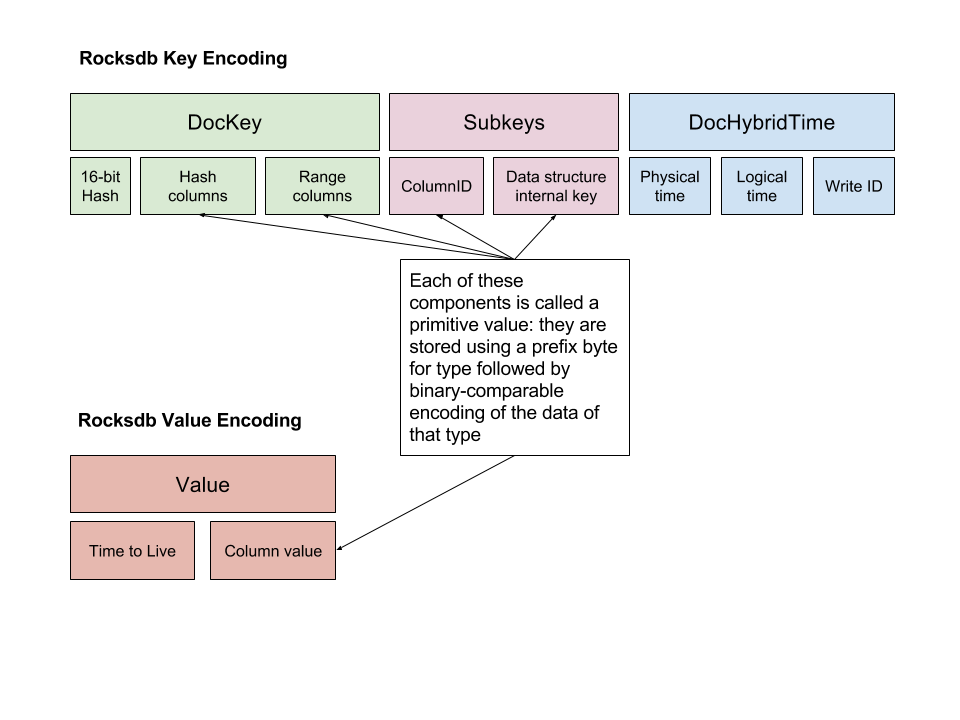

This storage layer is a persistent key-to-object (or to-document) store. The following diagram depicts the storage model where not every element is always present:

DocDB key

The keys in a DocDB document model are compound keys consisting of zero or more hash-organized components followed by zero or more ordered (range) components. These components are stored in their data type-specific sort order, with both ascending and descending sort order supported for each ordered component of the key. If any hash columns are present then they are preceded by a 16-bit hash of the hash column values.

If colocation is being used then the key will be prefixed with the colocation ID of the table it is referring to (not shown in the diagram); this separates data from different tables colocated in the same tablet.

DocDB value

The values in a DocDB document data model can be of the following types:

- Primitive types, such as int32, int64, double, text, timestamp, and so on.

- Non-primitive types (sorted maps), where objects map scalar keys to values that could be either scalar or sorted maps.

This model allows multiple levels of nesting and corresponds to a JSON-like format. Other data structures such as lists, sorted sets, and so on are implemented using DocDB’s object type with special key encodings. In DocDB, hybrid timestamps of each update are recorded carefully, making it possible to recover the state of any document at some point in the past. Overwritten or deleted versions of data are garbage-collected as soon as there are no transactions reading at a snapshot at which the old value would be visible.

Encoding documents

The documents are stored using a key-value store based on RocksDB, which is typeless. The documents are converted to multiple key-value pairs along with timestamps. Because documents are spread across many different key-values, it is possible to partially modify them without incurring overhead.

The following example shows a document stored in DocDB:

DocumentKey1 = {

SubKey1 = {

SubKey2 = Value1

SubKey3 = Value2

},

SubKey4 = Value3

}

Keys stored in RocksDB consist of a number of components, where the first component is a document key, followed by several scalar components, and finally followed by a MVCC timestamp (sorted in reverse order). Each component in the DocumentKey, SubKey, and Value, are PrimitiveValues, which are type value pairs that can be encoded to and decoded from byte arrays. When encoding primitive values in keys, a binary-comparable encoding is used for the value, so that sort order of the encoding is the same as the sort order of the value.

Updates and deletes

Suppose the document provided in the example in Encoding documents was written at time T10 entirely. Internally that document is stored using five RocksDB key value pairs, as per the following:

DocumentKey1, T10 -> {} // This is an init marker

DocumentKey1, SubKey1, T10 -> {}

DocumentKey1, SubKey1, SubKey2, T10 -> Value1

DocumentKey1, SubKey1, SubKey3, T10 -> Value2

DocumentKey1, SubKey4, T10 -> Value3

Deletions of documents and subdocuments are performed by writing a single Tombstone marker at the corresponding value. During compaction, overwritten or deleted values are cleaned up to reclaim space.

Mapping SQL rows to DocDB

For YSQL and YCQL tables, every row is a document in DocDB.

Primary key columns

The document key contains the full primary key with column values organized in the following order:

- A 16-bit hash of the hash column values is stored if any hash columns are present.

- The hash columns are stored.

- The clustering (range) columns are stored.

Each data type supported in YSQL or YCQL is represented by a unique byte. The type prefix is also present in the primary key hash or range components.

Non-primary key columns

The non-primary key columns correspond to sub-documents in the document. The sub-document key corresponds to the column ID. There's a unique byte for each data type we support in YSQL (or YCQL). The values are prefixed with the corresponding byte. If a column is a non-primitive type (such as a map or set), the corresponding sub-document is an Object.

A binary-comparable encoding is used for translating the value for each YCQL type to strings that are added to the key-value store.

Packed row format (Beta)

A row corresponding to the user table is stored as multiple key value pairs in the DocDB. For example, a row with one primary key K and n non-key columns , that is, K (primary key) | C1 (column) | C2 | ……… | Cn, would be stored as n key value pairs - <K, C1> <K, C2> .... <K, Cn>.

With packed row format, it would be stored as a single key value pair: <K, packed {C1, C2...Cn}>.

While UDTs (user-defined types) can be used to achieve the packed row format at the application level, native support for packed row format has the following benefits:

- Lower storage footprint.

- Efficient INSERTs, especially when a table has large number of columns.

- Faster multi-column reads, as the reads need to fetch fewer key value pairs.

- UDTs require application rewrite, and therefore not necessarily an option for all use cases, like latency sensitive update workloads.

The packed row format can be enabled using the Packed row flags.

Design

Following are the design aspects of packed row format:

-

Inserts: Entire row is stored as a single key-value pair.

-

Updates: If some column(s) are updated, then each such column update is stored as a key-value pair in DocDB (same as without packed rows). However, if all non-key columns are updated, then the row is stored in the packed format as one single key-value pair. This scheme adopts both efficient updates and efficient storage.

-

Select: Scans need to construct the row from packed inserts as well as non-packed update(s), if any.

-

Point lookups: Point lookups will be just as fast as without packed row as fundamentally, we will still be seeking a single key-value pair from DocDB.

-

Compactions: Compactions produce a compact version of the row, if the row has unpacked fragments due to updates.

-

Backward compatibility: Read code can interpret non-packed format as well. Writes/updates can produce non-packed format as well. Once a row is packed, it cannot be unpacked.

Performance data

Testing the packed row feature with different configurations showed significant performance gains:

- Sequential scans for table with 1 million rows was 2x faster with packed rows.

- Bulk ingestion of 1 million rows was 2x faster with packed rows.

Limitations

The packed row feature works for the YSQL API using the YSQL-specific GFlags with most cross features like backup and restore, schema changes, and so on, subject to certain known limitations which are currently under development:

- #15143 Colocated and xCluster - There are some limitations around propagation of schema changes for colocated tables in xCluster in the packed row format that are being worked on.

- #14369 Packed row support for YCQL is limited and is still being hardened.

Data expiration in YCQL

In YCQL, there are two types of TTL: the table TTL, and column-level TTL. Column TTLs are stored with the value using the same encoding as Redis. The table's TTL is not stored in DocDB (instead, it is stored in the master's syscatalog as part of the table's schema). If no TTL is present at the column's value, the table TTL acts as the default value.

Furthermore, YCQL has a distinction between rows created using Insert vs Update. YugabyteDB keeps track of this difference (and row-level TTLs) using a "liveness column", a special system column invisible to the user. It is added for inserts, but not updates, which ensures the row is present even if all non-primary key columns are deleted only in the case of inserts.

Collection type examples for YCQL

Consider the following YCQL table schema:

CREATE TABLE msgs (user_id text,

msg_id int,

msg text,

msg_props map<text, text>,

PRIMARY KEY ((user_id), msg_id));

Insert a row

T1: INSERT INTO msgs (user_id, msg_id, msg, msg_props)

VALUES ('user1', 10, 'msg1', {'from' : 'a@b.com', 'subject' : 'hello'});

The entries in DocDB would look similar to the following:

(hash1, 'user1', 10), liveness_column_id, T1 -> [NULL]

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_column_id, T1 -> 'msg1'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'from', T1 -> 'a@b.com'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'subject', T1 -> 'hello'

Update subset of columns

The following example updates a subset of columns:

T2: UPDATE msgs

SET msg_props = msg_props + {'read_status' : 'true'}

WHERE user_id = 'user1', msg_id = 10

The entries in DocDB would look similar to the following:

(hash1, 'user1', 10), liveness_column_id, T1 -> [NULL]

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_column_id, T1 -> 'msg1'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'from', T1 -> 'a@b.com'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'read_status', T2 -> 'true'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'subject', T1 -> 'hello'

Update entire row

The following example updates an entire row:

T3: INSERT INTO msgs (user_id, msg_id, msg, msg_props)

VALUES (‘user1’, 20, 'msg2', {'from' : 'c@d.com', 'subject' : 'bar'});

The entries in DocDB would look similar to the following:

(hash1, 'user1', 10), liveness_column_id, T1 -> [NULL]

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_column_id, T1 -> 'msg1'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'from', T1 -> 'a@b.com'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'read_status', T2 -> 'true'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'subject', T1 -> 'hello'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), liveness_column_id, T3 -> [NULL]

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_column_id, T3 -> 'msg2'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_props_column_id, 'from', T3 -> 'c@d.com'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_props_column_id, 'subject', T3 -> 'bar'

Delete a row

The following example deletes a single column from a row:

T4: DELETE msg_props

FROM msgs

WHERE user_id = 'user1'

AND msg_id = 10;

Even though in the preceding example the column being deleted is a non-primitive column (a map), this operation only involves adding a delete marker at the correct level, and does not incur any read overhead. The logical layout in DocDB at this point should be similar to the following:

(hash1, 'user1', 10), liveness_column_id, T1 -> [NULL]

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_column_id, T1 -> 'msg1'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, T4 -> [DELETE]

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'from', T1 -> 'a@b.com'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'read_status', T2 -> 'true'

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_props_column_id, 'subject', T1 -> 'hello'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), liveness_column_id, T3 -> [NULL]

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_column_id, T3 -> 'msg2'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_props_column_id, 'from', T3 -> 'c@d.com'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_props_column_id, 'subject', T3 -> 'bar'

The key-value pairs that are displayed in strike-through font are logically deleted. The preceding DocDB layout is not the physical layout per se, as the writes happen in a log-structured manner.

When compactions occur, the space for the key-value pairs corresponding to the deleted columns is reclaimed, as per the following:

(hash1, 'user1', 10), liveness_column_id, T1 -> [NULL]

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_column_id, T1 -> 'msg1'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), liveness_column_id, T3 -> [NULL]

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_column_id, T3 -> 'msg2'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_props_column_id, 'from', T3 -> 'c@d.com'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_props_column_id, 'subject', T3 -> 'bar'

T5: DELETE FROM msgs // Delete entire row corresponding to msg_id 10

WHERE user_id = 'user1'

AND msg_id = 10;

(hash1, 'user1', 10), T5 -> [DELETE]

(hash1, 'user1', 10), liveness_column_id, T1 -> [NULL]

(hash1, 'user1', 10), msg_column_id, T1 -> 'msg1'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), liveness_column_id, T3 -> [NULL]

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_column_id, T3 -> 'msg2'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_props_column_id, 'from', T3 -> 'c@d.com'

(hash1, 'user1', 20), msg_props_column_id, 'subject', T3 -> 'bar'

TTL examples for YCQL

The following are the two types of TTL used in YCQL:

- Table-level TTL: YCQL allows the TTL property to be specified at the table level. In this case, TTL is not stored on a per key-value pair basis in RocksDB; instead, TTL is implicitly enforced on reads and during compactions to reclaim space.

- Row- and column-level TTL: YCQL allows the TTL property to be specified at the level of each

INSERTandUPDATEoperation. In such cases, TTL is stored as part of the RocksDB value.

The following example demonstrates use of the row-level TTL:

CREATE TABLE page_views (page_id text,

views int,

category text,

PRIMARY KEY ((page_id)));

Insert row with TTL

The following example inserts a row with TTL:

T1: INSERT INTO page_views (page_id, views)

VALUES ('abc.com', 10)

USING TTL 86400

The entries in DocDB should look similar to the following:

(hash1, 'abc.com'), liveness_column_id, T1 -> (TTL = 86400) [NULL]

(hash1, 'abc.com'), views_column_id, T1 -> (TTL = 86400) 10

Update row with TTL

The following example updates a row with TTL:

T2: UPDATE page_views

USING TTL 3600

SET category = 'news'

WHERE page_id = 'abc.com';

The entries in DocDB should look similar to the following:

(hash1, 'abc.com'), liveness_column_id, T1 -> (TTL = 86400) [NULL]

(hash1, 'abc.com'), views_column_id, T1 -> (TTL = 86400) 10

(hash1, 'abc.com'), category_column_id, T2 -> (TTL = 3600) 'news'